Losing Your Concentration

by Juan Ros | May 18, 2017 2:40 pm

Using philanthropy to diversify and generate income is easier than you think.

Do you own too much of a good thing? One of the keys to successful long-term investing is diversification—owning enough of different kinds of investments so that your entire portfolio doesn’t move in the same direction (up or down) at the same time.

Sometimes, whether through inheritance, a long-ago purchase, or sale of a business, you may find yourself holding a single stock that makes up a substantial portion of your overall portfolio—known as a concentrated position. Generally, holding a concentrated position is not wise.

If that stock is held in a taxable account, and it has appreciated significantly since first acquired, the tax alone might be enough to keep you from selling the stock, even though selling and diversifying would be in your best interest and would reduce the risk in the portfolio.

Another objection to selling: you may be relying on the dividends from that stock for income.

Fortunately, charitable strategies can be employed to allow an investor to sell a concentrated position, defer the capital gains tax that would otherwise be due on the sale, generate income, and receive a charitable deduction, all in one fell swoop.

First up: the charitable gift annuity.

What is a Charitable Gift Annuity?

A charitable gift annuity (“CGA” for short) is a contractual arrangement between a donor and a charity whereby the donor gives cash, securities, or other assets to the charity in exchange for the payment of income for life.

The amount of annuity income paid by the charity is dependent on the age of the donor—the older the donor, the more income gets paid. Most charities use a standard table of annuity rates published by the American Council on Gift Annuities and updated regularly.

Case Study—Charitable Gift Annuity

[1]

[1]

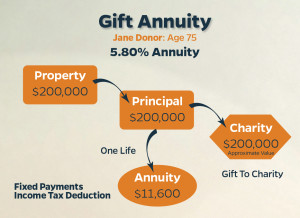

Illustration A: Charitable Gift Annuity Case Study

Illustration A shows how the CGA can be used to diversify a concentrated position:

Assume Jane Donor, age 75, owns 1,000 shares of Company X that she bought at $10 per share many years ago. Shares are now selling for $200—a $190/share profit. Jane’s portfolio, valued at $2 million, consists of a broad range of mutual funds, but she holds Company X because she doesn’t want to pay the tax on the gain. Company X makes up 10% of her portfolio—a concentrated position. Company X’s dividend yield is 2%.

Jane decides to establish a charitable gift annuity with her alma mater, and fund the annuity with her Company X shares. She delivers the shares electronically to her alma mater’s brokerage account—her portfolio is now worth just $1.8 million, but she no longer has a concentrated position.

At age 75, Jane’s published gift annuity rate is 5.8%, meaning her alma mater will pay her $200,000 x 5.8% = $11,600 per year income for life—more than she was receiving from the Company X dividend.

With a CGA, capital gains that would normally have been due upon the sale of a security are paid out in installments over the life expectancy of the donor. In this case, roughly $8,300 of each annual payment is taxed at favored capital gains rates for the next 12 years. The remainder of the income payment is part ordinary income and part tax-free return of principal.

Jane also gets a charitable deduction of $91,543 (assumes 2.4% AFR) which she can use to offset her income this year. To the extent that she can’t absorb the entire deduction, the unused amount gets carried forward for up to five additional years.

And, Jane gets to make a major gift to her alma mater, which keeps whatever amount remains from the original gift after Jane passes away.

This is the only drawback to the CGA, from the donor’s perspective: if the donor passes away early during the annuity period, the annuity ends and the charity “wins.” CGAs can be established to benefit a husband and wife for their joint life expectancy, but the joint annuity rates will be lower than those for a single individual.

Summary of CGAs

Consider a charitable gift annuity to help diversify a concentrated position if:

- You are charitably inclined;

- You are at least 60 years old (most charities that offer CGAs have minimum age requirements);

- You want a simple, hassle-free way of achieving greater diversification in your portfolio;

- You are relying on income from the concentrated position.

An alternative to the charitable gift annuity that offers more flexibility (at a price) is the charitable remainder trust.

What is a Charitable Remainder Trust?

A charitable remainder trust (“CRT”) is an arrangement that provides for a specific amount of income to be paid to one or more income beneficiaries. The trust is funded using cash, securities, real estate, or other assets. After the income period ends, the trust terminates and the assets remaining in the trust are distributed to one or more charities.

The CRT allows for much greater design flexibility than the gift annuity: the donor can choose the percentage of the trust assets to be paid as income; the donor can choose, within certain limits, how long the trust will last; the donor can choose the charities receiving the remaining assets and can even reserve the right to change the charitable recipients of the trust.

The CRT requires greater expense and administration than the gift annuity (which doesn’t cost the donor anything). An attorney is needed to draft the CRT document, and a CPA / third-party administrator who specializes in charitable trusts is needed to ensure all tax forms are filed properly. An investment advisor is needed to manage the trust assets and ensure the income beneficiaries are paid as dictated by the trust.

Despite the added effort, a CRT can work effectively to diversity a single stock position or several concentrated positions in an investor’s portfolio.

Case Study—Charitable Remainder Trust

[2]

[2]

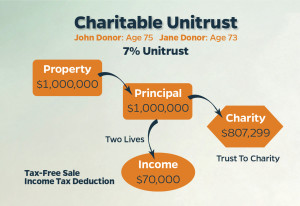

Illustration B: Charitable Remainder Trust Case Study

Illustration B shows how the CRT can be used to diversify a concentrated position:

Assume John Donor, age 75, owns 5,000 shares of Company Y that he bought at $10 per share many years ago. Shares are now selling for $200—a $190/share profit. John’s portfolio, valued at $5 million, otherwise consists of a broad range of mutual funds, but he holds Company Y because he doesn’t want to pay the tax on the gain. Company Y makes up 20% of his portfolio—a highly concentrated position. Company Y’s dividend yield is 2%.

John decides to establish a charitable remainder trust and fund the CRT with his Company Y shares. He hires an attorney to draft the trust and delivers the shares electronically to a brokerage account registered to the trust. John serves as trustee of the CRT.

Once inside the CRT, the concentrated position is sold without incurring capital gains and reinvested in a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds. Once that happens, John no longer has a concentrated position.

John decides to have the CRT pay 7% of the trust’s value, as revalued each year, annually to him and his wife, age 73, for their joint lives. John and his wife will receive $1,000,000 x 7% = $70,000 in the first year, and a varying amount in subsequent years (depending on the trust’s investment performance), as long as either is alive—more than he was receiving from the Company Y dividend.

With a CRT, capital gains that would normally have been due upon the sale of a security are deferred and instead are paid out in installments with each trust payment until the entire gain has been distributed. CRTs have a complex taxation structure, but suffice to say that the annual income will be taxed partly as ordinary income, to the extent the trust investments generate income, and partly as capital gains—including the gains from the sale of the concentrated position.

John also gets a charitable deduction of $358,560 (assumes 2.4% AFR) which he can use to offset his income this year. To the extent that he can’t absorb the entire deduction, the unused amount gets carried forward for up to five additional years.

And, John and his wife choose to divide the remainder interest among three charities—a local animal shelter, the area hospital on whose board John sits, and their church as the third.

The end result is similar to that of the gift annuity: the removal of the concentrated stock position, increased income, deferred capital gains, a charitable deduction, and a major gift to charity.

Summary of CRTs

Consider a charitable remainder trust to help diversify a concentrated position if:

- You are charitably inclined;

- You desire flexibility in the design of the diversification strategy;

- Your stock position is significant enough to justify the additional expense necessary to establish and administer a CRT;

- You are relying on income from the concentrated position.

Whether a gift annuity or a remainder trust—for those who are philanthropic, there is no excuse for keeping a concentrated stock position in your investment portfolio. •

- [Image]: http://www.socalprofessional.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Southern-California-Professional-Gift-Annuity-Juan-Ros.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.socalprofessional.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Southern-California-Professional-Charitable-Trust-Juan-Ros.jpg

Source URL: http://www.socalprofessional.com/2017/05/losing-your-concentration-2/